Last week was one of the best on recent record for both stock and bonds. The S&P 500 gained nearly 6%, erasing more than half of its correction (-11%), while the US 10-year Treasury gained 2% and the 30-year gained 4%, now trading at 4.6% and 4.7% respectively.

The ostensible catalyst was the Fed’s second-in-a-row rate pause, accompanied by comments which led markets to believe the US central bank is done with rate hikes for this cycle –and that we could see rate cuts at some point mid-next year.

Friday’s slightly below-expectation labour market numbers helped further fuel those hopes. In addition, bond futures had a lot of short positions, which allowed for a short squeeze (traders giving up on their bets against bonds).

However, the last week of October is the last week of trading for Hedge Funds and other investment vehicles in the financial year. As such, many move to crystallise losses. On 1 November, managers wipe the slate clean and are free to trade again.

Historically, this has been very well documented. In the last 52 years, for the S&P 500:

- 75% of returns after Nov 1 through to the end of the year have been positive.

- When returns are positive, the last two months count for more than 30% of annual returns for the index on average.

- 29% of the time, the last two months have had better performance than the previous ten months cumulatively.

- Results are less clear in other markets, which may correlate with the S&P but don’t have the same fiscal year.

In an age where robots run trading, it stands to reason that past trends would tend to be reinforced. Thus, the combination of a rate pause confirmation along with a fiscal year-end for funds and short positioning catalysed a broad-based asset rally.

The next big question for investors is: when are the rate cuts? A market expectation of ten months seems reasonable on paper.

However, in this writer’s humble opinion, investors betting heavily on a half-year rate cut could be rushing things.

For one, while there is a high probability of a rate cut, we do live in a world that is geopolitically fraught. The US is already running a 6.7% budget deficit, and we are entering an election year. Yes, House Republicans are unlikely to do Joe Biden any further fiscal favours, but wars in Israel and Ukraine cost money. The Republican party has generally been more in favour of military spending historically. The added bonus is that military support in the Middle East is costing Democrats votes in key battleground states ahead of the election. So, perversely, both sides might agree to further fiscal expansion.

An independent Fed might try to counterbalance more fiscal spending, either by increasing rates again or at least keeping them higher for even longer – which has a similar effect.

Secondly, rate hikes aren’t the be-all-and-end-all. Money can still get more expensive, as the Fed doesn’t control the long end of the curve. With debt levels rising, possibly because of even more issuance, the Fed not buying and Emerging Markets trying to wean themselves off the greenback, debt supply and demand dynamics are simply not favourable.

And don’t forget inflation. Higher inflation is still very much on the table, and it also lives at the longer end of the curve. The Fed cutting rates might help short yields, but longer-term investors who will see higher prices and a passive Fed might decide to disinvest, pushing yields even higher. Despite last week’s action, and barring a big financial accident, long yields could keep rising, or at least staying at high levels, even if the Fed does nothing, or even begins to cut short rates carefully.

Thirdly, markets are bad at predicting rates. Bullishness may be good for stocks, but it might not work for bonds. And it certainly doesn’t work for rate expectations. In the past year and a half, investors have grossly underestimated the Fed’s rate intentions. This time last year, markets were pricing in the first-rate cuts as early as September 2023 (when rates in fact peaked). Two years ago, a maximum of two rate cuts was predicted for 2022. Five months later, when the Fed had declared that it aimed to fight inflation and the war in Ukraine had erupted, no more than five hikes were priced in. The Fed ended up hiking 17 times!

So, in conclusion, the Santa rally could be already here, as it is most years. A good part of that may have already happened last week, although history suggests there could be more. But that is very much a trading and past trends exercise. Equity and bond investors counting on swift rate cuts would do well to remember that their scenario might not necessarily be one of linear normality. It is more likely that they are betting on a financial accident, or some other sort of issue that would force central banks to perform emergency rate cuts.

George Lagarias, Chief Economist

Market update

US equities had their best week of 2023 so far, rising by +5.9% in USD terms (+3.7% in GBP) last week, as statements made by the Federal Reserve were viewed as dovish. While the Fed kept interest rates steady at its policy meeting on Wednesday, markets were encouraged by the acknowledgement that the recent rise in longer-term bond yields had served to advance some of the Fed’s goals in tightening financial conditions.

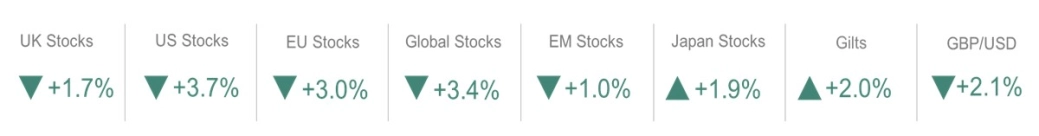

Macroeconomic factors, including cooling employment and PMI data, added fuel to the rally as investors were reassured that the end of rate hikes had come. Stocks in other regions joined in the upswing, with global equities rising by +3.4% and positive returns seen in UK, EU, Japan, and emerging markets indices.

Bonds performed well over the week in the UK and US, with yields falling around 25 bps each. Meanwhile in Japan, long bond yields spiked to ten-year highs after the Bank of Japan modified its yield curve control policy, no longer capping 10-year bonds at 1.0%. Subsequently the yield on the 10-year bond peaked at 0.97% on Wednesday.

Macro news

US non-farm payrolls, a key measure of the tightness of the US labour market, were reported to have increased by 150,000 in October. This was lower than analyst expectations and significantly less than the 297,000 jobs added in September. This, in conjunction with a slight rise in unemployment to 3.9%, indicates that interest rate hikes are beginning to have their desired impact – slowing down economic activity. Businesses are growing more cautious on new hires as economic uncertainty hits their operations. Wage pressures in the US are also easing, with US average hourly earnings rising +4.1% on a year-on-year basis in October, down from +4.3% in September.

Meanwhile, European economic activity is decelerating rapidly. The HCOB Eurozone Composite PMI Output Index fell to 46.5 in October, as both the manufacturing and services sectors contracted due to a worsening demand picture. Headline EU inflation also fell to 2.9% in October, driven primarily by a sharp fall in energy costs.

The week ahead

Official estimates for UK GDP growth in Q3 will be released on Friday this week. Analysts are anticipating a mild contraction of 0.1% for the UK economy on a quarter-on-quarter basis. Meanwhile, US initial jobless claims, released on Thursday, will be a useful indicator of US labour market activity.

Economy and investment webinar

On Wednesday 29 November, join our Chief Economist and Chief Investment Officer as they discuss the current economic landscape, both here in the UK and globally.

Register here