A briefing on proposed withdrawals from the ECT

As countries endeavour to meet increasingly ambitious emission targets, many consider withdrawing from the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). However, with member parties bound by a 20 year sunset clause, is this the right decision?

Why are countries withdrawing from the Energy Charter Treaty?

The last two weeks have seen Spain, the Netherlands and France state their intentions to withdraw from the Energy Charter Treaty (“ECT” or “Agreement”), this follows from Poland withdrawing in September 2022. As it stands Italy is the only country to have withdrawn, doing so in 2016, but is still bound by the 20 year sunset clause.

The primary reason for withdrawing appears to be due to the incompatibility of the ECT with the Paris Agreement and need to act on climate change as currently the ECT provides protection to investors for carbon-emitting investments.

What is the ECT?

The ECT was signed by 53 parties in December 1994 and came into force in April 1998. It was designed for the promotion of international cooperation in the energy sector.

In order to promote cross-border investments the parties to the Agreement are to make every effort to provide a stable and transparent legal framework for foreign investments. The ECT also states the importance of access to adequate dispute settlement mechanisms, including national mechanisms and international arbitration in accordance with arbitration laws, relevant bilateral and multilateral treaties and international agreements. This provides investors with protection to claim compensation from the parties to the ECT.

The past and current claims made under the ECT

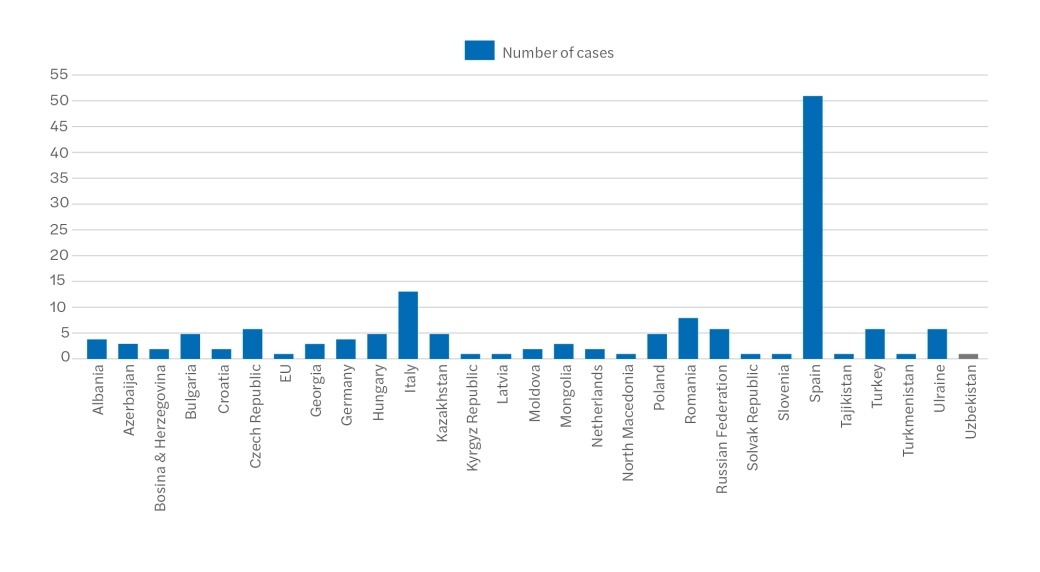

Spain and Italy have faced the most claims by investors under the ECT as follows:

Figure 1: Number of cases invoking the ECT [1]

[1] https://www.energychartertreaty.org/cases/statistics/

One of the key reason countries such as Spain and Italy have high numbers of claims invoking the ECT is due to retrospective changes to the generous incentives that these countries originally implemented to attract investors to renewable energy projects. These retrospective changes occurred in 2013 for both Spain and Italy, for example, by reducing the feed-in-tariffs they paid to renewable energy producers. The increase in renewable energy claims can be seen in the figure below which shows the ECT invoked actions by sub-sector and year.

Figure 2: Breakdown of cases by year and sub-sector [2]

[2] https://www.energychartertreaty.org/cases/statistics/

It can be seen that more recently the ECT has provided a greater number of investors in the renewable energy sector with legal protection than those in the fossil fuel sector.

Attempts to modernise the ECT

The countries attempting to withdraw from the ECT appear to be more concerned about future claims that are going to arise under the ECT as a result of acting on climate change. For example, in February 2021, RWE, a German utility company filed suit against the Netherlands government under the ECT alleging that the Netherlands have not provided adequate time to transition away from coal. As the Netherlands have committed to phase out all coal-fired power plants by 2030 this will allegedly not provide adequate compensation for RWE, which owns the Eemshaven power plant.

To combat these concerns, there has recently been a drive to modernise the ECT. On 24 June 2022, there was an agreement in principle concluding negotiations on a modernised ECT. This agreement in principle includes a “flexibility mechanism” which allows the parties to exclude investment protection for fossil fuels in their own territories. The EU and UK have opted to carve-out fossil fuel related investments from protection under the ECT. However, this only excludes them after 10 years of the modernised ECT coming into force and excludes new investments made after August 2023 [3]. Therefore, any fossil fuel investments made prior to August 2023 appear to be protected for a 10 year period commencing on signing of the modernised agreement.

There are concerns this modernisation does not go far enough and still provides protection for fossil fuel investments, potentially impacting the ability of parties under the ECT to push on with climate friendly laws and regulations without facing the risk of significant litigation from fossil fuel investments.

[3] https://www.energychartertreaty.org/modernisation-of-the-treaty/

What are the implications of withdrawing from the ECT?

The withdrawal from the ECT by any members would appear to trigger a sunset clause which means any investments made up until the date of the withdrawal are still protected for a period of 20 years. Italy appears to be subject to this sunset clause as they have received a number of ECT claims since their withdrawal in 2016, including the recent Award made to Rockhopper (a UK oil and gas exploration company) of €190m in relation to Italy banning new oil and gas projects within 12 miles of its coast in 2015.

Therefore, it appears withdrawal will only really have an impact either 20 years after withdrawal or on any new investments made post withdrawal. Given climate change targets and the intentions for withdrawal of the ECT it could be assumed that future investments in fossil fuels are likely to be minimal in comparison to investments in renewable projects going forward in any event.

It also appears that any investments made in renewable energy projects post withdrawal of the ECT will not have the protection of the ECT or modernised ECT. Whereas remaining part of a modernised ECT (as drafted in its current form) appears to still give protection to renewable energy projects going forward indefinitely, whilst allowing parties to limit protection to fossil fuel investments for a period of only 10 years.

With no protection for new investments made after the withdrawal, investors may need to look for alternative protections for their investments, for example other Bilateral Investment Treaties. It could therefore be possible that complete withdrawal may impact on the attractiveness of investments into those countries for renewable projects if investors do not feel protected enough. Furthermore, if parties could withdrawal from the ECT without a sunset clause this would appear to allow them more flexibility in changing regulations for climate change without fear of fossil fuel investments invoking the ECT.

[Disclaimer for charts above]

This work is partially based on the statistics of legal cases as developed by the ECS but the resulting work has been prepared by Mazars LLP and does not necessarily reflect the views of the ECS