Bond investors are sitting on a loss after five years. Now what?

Bond investors are sitting on a loss after 5 years

Yet, in finance, there are two main building blocks: Equities, a share in a corporation and its profitability, and fixed income, or bonds, a debt owed to investors by governments or corporations. While the former is considered more “exciting” and newsworthy, due to its unpredictability and volatility, the latter is bigger, more complex and vastly more important to the global economy.

And, unlike equities, it is not in a bull market.

But let’s take it from the top. The size of the global bond market is approximately $135tn, 15% higher than the total capitalisation of global equities ($117tn at the time of writing). Because of their nature, that of a predictable income if held to maturity, they are the preferred asset class of central banks, commercial banks and, most importantly, pension funds. A 2022 survey of 1000 US pension funds showed that over 50% of holdings were in fixed income, 25% in equities, and about 15% in illiquid investments (we should circle back to that in a future note).

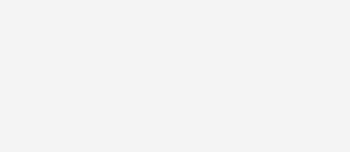

Since 2009, central banks had been pushing yields lower, to make risk more attractive to investors by making sure borrowing costs remained low. This drove institutional investors, who prefer the asset class, to increase both their exposure and their leverage in fixed income, in an effort to squeeze returns out of increasingly lower yields and meet their obligations. The alternative would have been an increase of either equity (which would mean a massive change in portfolio volatility) or an increase in illiquid instruments, where risks would become more substantial in a liquidity crunch. At the beginning of 2021, a record $18tn bonds had a negative yield, which meant investors were buying them only for the capital return and not the yield.

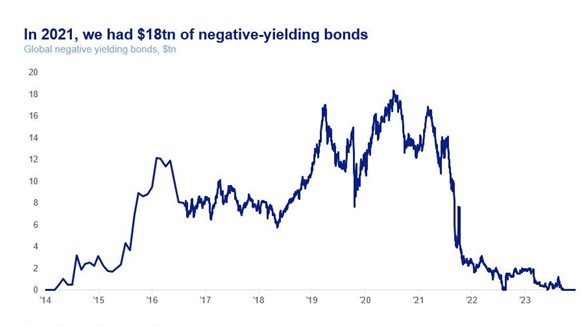

2021 was a disappointing year, as the pandemic struck disrupting all markets. A year after that, the bond apocalypse struck. Central banks, having lost control of inflation, began hiking rates aggressively. Investors had gotten used to the Federal Reserve taming the yield curve for over 15 years. The abruptness by which the Fed abandoned that role, caused a massive and historically unprecedented re-rating of fixed-income instruments worldwide. The Global Aggregate Index lost 16%, three times more than any previous shock.

Whereas the fixed income market recovered, somewhat, in 2023, 2024 has again been disappointing, as investors' hopes for a fast de-escalation of high rates have been quashed by persistent US inflation.

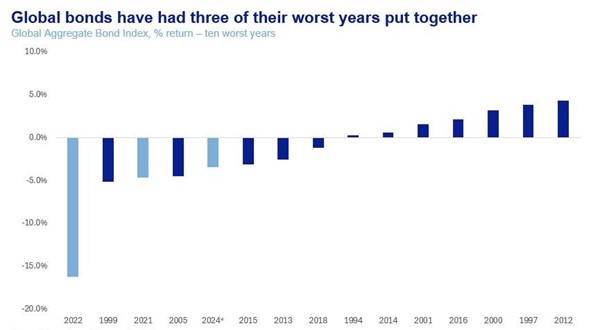

Patient investors are told that they should wait at least five years before assessing the course of their investment. Since December 2019, just before the pandemic, aggregate fixed income has lost 11% whereas global equities have gained 55%. This is 10.6% per annum for equities and -2.6% for bonds.

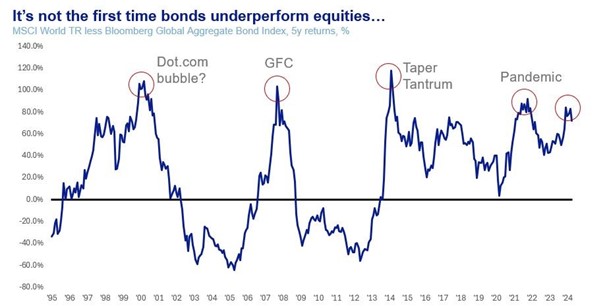

The equity/bond differential has been this broad a few times in the past. Mostly in the runup of the 2000 and 2008 equity crash, following the 2013 “taper tantrum” and during the pandemic. Three of those times were due to massive equity rallies, and two were due to bond crunches.

But never, in modern monetary times (since 1971) has 5y bond performance been negative, especially for US Treasuries, the cornerstone of most institutional global portfolios.

So what is it that investors need to know? Are bonds dead?

The long and short of it is: no, they are not.

Unlike equities, bonds have a yield. Anthony Peters, our esteemed and senior external investment committee member, often reminds us that bonds are held for the yield, not the capital return. At a near 5% yield, and with inflation coming closer to being under control, the real yield is positive. And while the Fed has paused rates for now, eventually it will have to lower rates.

- For one, they are currently way above the average natural rate of interest (the one that neither constricts nor stimulates the economy, known as R-Star), which has been estimated just north of 1% by the Federal Bank of New York a few months ago.

- Second, high rates are not helpful in a high-debt world. If the US has to pay 3.5% of its GDP in interest payments while only growing by 2%-2.5%, then high rates are simply not sustainable. If rates come down, bondholders should see some capital appreciation as well.This provides solace going forward, but what about losses already incurred? Will investors make their losses up?

Again, while it is hard to say, we don’t expect a return of rates back to zero, $20tn of negative-yielding bonds, bar a significant financial incident. So no, the losses won’t likely be made up anytime soon. Negative 5-year bond returns are the result of central bank excesses in the years that preceded 2022, the result of which was a re-rating. Higher yields put a natural cap on how far the rerating can proceed, but full-mean reversion is, at best, a low-probability event.

So what do we tell defensive investors?

Defensive portfolios, owned by clients who spent the last five years reading about the pandemic and increasing global risks have been hit the hardest, as they have the highest bond exposure. Up to a point, this is natural, as it was the emergence of inflation that delivered the blow, and inflation tends to be kinder to equities than bonds.

But it does beg the question? What is “defensive”?

Theory tells us that “Defensive” is “less volatile”. Back in the 1950s, the late Harry Markowitz came up with his “Modern Portfolio Theory”, (MPT). This was an attempt to re-introduce savers and pensioners to investments after they had been wiped out by the 1929 crash, the Great Depression and the Second World War. Markowitz put science in what was, until then, a brokerage and sales profession, rightly earning a Nobel prize for his work. He equated “risk” to portfolio volatility as a key source of anxiety for investors.

For its time, this was great. But markets have become much deeper and more complex in the last 70 years. The ‘normal distribution’, a simplified statistical framework that underpins MPT, has been challenged by reality and observation.

For equities, volatility works. Not so for bonds. In the past five years, the volatility of equities has been 21% and for bonds less than 4%. Yet the former gained 55% while the latter lost 11%.

Are bonds “safer”? Markowitz would argue “yes”.

But in 2021, our investment committee made the decision to ignore historical volatility and simply look at what was in front of it: an asset class with near-zero yield, inflation getting away and the Fed sharpening its teeth for rate hikes. Risk wasn’t just about volatility but about the downside, which is how most people see it. A simple risk-reward analysis suggested that we remain massively underweight bonds and reduce duration as much as possible. This allowed us to mitigate the worst aspects of the 2022 bond crash. We treated bonds as a yielding asset, not a capital appreciation asset. Volatility might as well be considered zero in this case, because our measure for “safety” was different. Could we have zeroed-out bonds? Technically yes, but there’s a difference between high conviction and prescience. We believed we knew how things would unfold, but could never claim to be certain.

Going forward, we don’t expect a quick fixed income rebound, but possibly a dragged-out one. It will take years for those who were fully exposed to the 2022 crash to recuperate their losses by being in a simple fixed-income portfolio.

As for investors? Mathematics, models and statistics make good informative tools for decision-makers, but risk must always be assessed in its entirety.

National contacts